Important News Concerning My Health

A Quick Intro to the Brilliance of Miles Davis

Town Hall Recap

Dear Families,

In case you missed it, below are the highlights from the Town Hall meeting on May 28 with Chris and me. In this segment, we discuss our broad-strokes thinking and planning for the fall. Our next Town Hall is on June 24 at 5:00 — see you then!

Thanks,

Jason

Patera’s Annual Dispensing of Unsolicited Advice

The Power of Momentum: How to Get Good at Something

For nearly 20 years before I became The Academy’s Head of School, I maintained a grueling roster of private piano students at my studio in the suburbs. Over the years, I had hundreds of students, and many developed into virtuoso musicians, won major scholarships and awards, and became successful professionals.I am not a virtuoso musician. My students excelled because I was able to help them develop momentum.

10 Academy Moments from the 2010’s That I Hope I Will Remember Forever

Showcase: More Than Just a Show

The 2019 Academy AIDS Benefit

Reverse the Headline

Reverse the Headline

You’ve probably seen the recent headline in Forbes magazine: High School Students Do Better In Science, Math And English If They Also Take Music Lessons. The article, like many dozens of others, summarizes research that shows how young people learning to play music perform better academically in school.

I’m often frustrated by the implication of this type of research. The message ends up being: “the arts are valuable because they make young people better at school.” While that is probably true, it is an ultimately dangerous message that makes the arts more vulnerable, not less. (If the job of a school’s arts program is to improve math scores, it’s at risk of being cut as soon as there’s a cheaper, quicker way to improve those same scores.)

Let’s reverse the headline: High school students who study math, science, and English make much better art.

At The Academy, we’ve long understood that the best art is made by the students most actively engaged in learning about the world they inhabit. And, we understand that their art is about far more than graduation requirements, ACT scores, and job prospects.

The arts are a critically important, non-negotiable part of living a good life. The arts inspire, unify, comfort, broaden perspective, heal, give voice, mobilize, and bring joy. In our darkest times, the arts remind us that we’re not alone. In difficult times, they help us understand one another. And in the best times, they amplify our joy.

As the legendary John Maeda (MIT scientist and former president of Rhode Island School of Design) writes:

“Amidst all the attention given to the sciences as to how they can lead to the cure of all diseases and daily problems of mankind, I believe that the biggest breakthrough will be the realization that the arts… will be recognized as the whole reason why we ever try to live longer or live more prosperously. The arts are the science of enjoying life.”

P.S. In case you missed last week’s post, click here to read Excellence, Purpose, and Passion.

Life at the Intersection of Excellence, Purpose, and Passion

Life at the Intersection of Excellence, Purpose, and Passion

Adapted from my TED Talk “Excellence, Purpose, and Passion,” (available online later this month) and from my welcome back remarks to students last week.

I knew that I was about to be humiliated the moment my classmate began her presentation.

I was in my early thirties and in a class for new and aspiring school leaders. The assignment was: “Prepare and Present Evidence of Student Achievement at Your School,” and as a veteran teacher and young administrator at a famous performing and visual arts high school, I was excited to advocate for the arts and an arts education. (I’ll admit I was also eager to show off dozens of photos of really cool young people doing epic work.)

Eager, for once in my life, to actually do some homework, I had prepared for my presentation with the same intensity I had practiced the piano in college. When presentation day came, I was inspired, I was prepared, and I was confident. That all changed the instant the first presenter began.

Remember the feeling you got in school when you were handing in a test, and the moment it was too late to change anything you realized you had done it all wrong? That’s how I felt.

In response to the prompt “show evidence of student achievement in your school,” my classmates were showing things like this:

Only then did it dawn on me that the words “student achievement” is usually a euphemism for “test scores,” and the presenters that day had all understood that their job was to show how well their schools’ students were doing on various state-mandated standardized tests.

I panicked. Even though our students tended to do really well on standardized tests, it had never occurred to me to use that data to try to prove that they were “achieving” anything.

I barely heard the discussion about percentiles and standards while I desperately tried to figure out what to do. I seriously considered feigning illness, pretending that my laptop was broken, or even just leaving.

But it was too late: it was my turn. I decided to just embrace it: ours has never been a typical school, and our students have never done “typical” work. In order to demonstrate “student achievement” in my school, I showed this:

This is a frame from a film made by Alex, who was (at the time) an 11th-grader in our Media Arts department. The film is called “A Starry Night,” and tells the story of a little boy whose mother has recently died. He lives in a bleak apartment with his father, and the two of them are trying — at times, desperately — to figure out how to be a family without Mom.

The little boy is obsessed with the idea of space travel. He spends his days dressed in a space suit playing with his spaceship toys; before bed time he stares out the windows, fixated on the stars in the night sky.

He longs to escape: literally, from the earth, and symbolically from the crushing weight of the loss he feels.

The film is brilliantly effective. It’s simultaneously heartbreaking and hopeful, bittersweet and joyful. At its premiere, the audience cried and laughed, everyone touched by Alex’s prodigious empathy.

By any measure that matters, the film was a success.

The arts teacher in me recognized the film as top-level work: technically and aesthetically virtuosic, it exceeded any requirements one could have possibly articulated in a rubric. The school administrator in me marveled at how, in the making of the film, Alex demonstrated all of the so-called “21st Century Skills” — leadership, collaboration, and creativity — that young people will need to be able to get jobs. But most importantly, the human being in me recognized Alex’s work for what it most truly was: the result of the relentless pursuit of excellence, in the context of finding purpose and feeling passion.

Excellence, purpose, and passion: what could possibly be better evidence of student achievement?

By that point, I had forgotten all about the dread I felt earlier, the shame in not having any spreadsheets, the fear of failing the assignment. I was caught up in the moment, still touched by Alex’s work. That is, until one of my classmates — a principal at another school — said, “I just don’t see how any of this is relevant. None of this is the real world. It’s like you’re all living in a fairy tale.”

To this day, I wonder: when did excellence, purpose, and passion become a “fairy tale”?

For decades at The Chicago Academy for the Arts, I’ve witnessed firsthand over and over again what happens when young people learn to do things that they believe matter, do things that they deeply enjoy doing, and do things that they are inspired to do really well.

They become people like Alex, whose powerfully empathetic storytelling about the dynamics of family, isolation, and loss — in the context day-to-day life and global events — has continued to move audiences long after high school.

Alex Girav’s Taksim Square

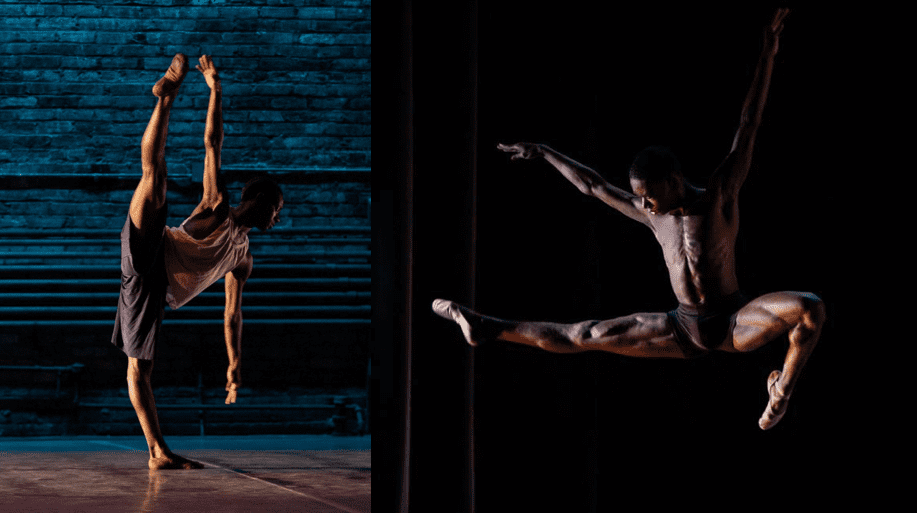

They become people like Amari, who has learned to not only defy gravity physically, but to defy the gravitational pull of “average.” At 18, he has already started a nonprofit to bring the joy of dance to those who are suffering. He is currently in his first year at Juilliard.

They become people like Maria, whose mission to “educate, heal, and inspire” has driven her to open music schools in two states. She recently was awarded a major “Educator of the Year” award.

And they become people like Justin, who is not only one of the most sought-after songwriters in the world today, but also an advocate and activist promoting inclusion, equality, and diversity in the music industry and beyond.

These four artists — and their hundreds of peers over the last two decades — have taught me that we find our best selves, and we live our best lives, in the pursuit of excellence, at the intersection of purpose and passion.

Our best lives are when we wake up hungry for what’s in front of us that day, because it’s more interesting than sleep; when we spend our time in a state of “flow” doing things that have personal and public meaning; when we collapse exhausted at the end of the day, not looking to escape, but in the satisfaction of knowing that we tried to do difficult things really well.

Everyone should know what this feels like.

However, many of us struggle to live our best lives, because we believe that voice in our head (or that voice in the room) that tells us about our limits. The voice that says, “You can’t write a book.” Or, “You can’t run a marathon.” Or, “You can’t start a business.” The voice that says, “you can’t be happy. You can’t make a difference. You can’t change the world.”

Many of us struggle to live our best lives, because we look for the wrong things: we’re duped into thinking that “success” means “more”: more money, more status, and more stuff. We’re conditioned to be “practical,” when for so many people “practical” means eschewing the very things that actually bring us joy in life.

And many of us struggle to live our best lives, because we live in fear of discomfort. We avoid the difficult conversation, the painful self-reflection, or the scary risk that might lead to failure. Instead, we embrace instant gratification and we endlessly scroll, we endlessly shop, and we endlessly... settle.

But there’s a way out.

In a long career of helping people of all ages learn how to act on their dreams, I’ve come to believe that there are three critical ingredients to living our best lives:

Reject mediocrity. Understand that most of what you think are your limits are illusions that will disappear once you start to truly challenge them. The problem is that coming face-to-face with our “limits” is hard, uncomfortable, and often scary. Embrace the discomfort necessary for doing hard things really well. Don’t settle: there’s magic on the other side.

Allow yourself to dream big and set ridiculous goals. Purpose and passion emerge when we approach each day with a commitment to curiosity, openness, and reflection. Make your journey your number-one priority and ask yourself, every day: What do I really want? Why do I want it? Am I telling the truth?

It may help to imagine that the older version of you already exists, and that they can write you a letter. What does Future You desperately wish you would start working on something today? Spend as much time as you can doing that.

3. Never allow your happiness to be contingent “achieving” anything. The novelty of accomplishment wears off shockingly fast, and when “new” becomes “normal,” we’re emotionally right back where we started.

Instead, fall in love with the journey, and with the process. Do you want to write a novel? Learn to love showing up at the page every single day. Do you want to run marathons? Learn to find joy somewhere in every early-morning or late-night training mile. Do you want to start a nonprofit? How many days in a row can you find an hour or three to fine-tune your plan to make a difference?

Today, I challenge you to reject mediocrity, reject your limits, dream big, and love the journey. May we all find excellence, purpose, and passion.

37 Seconds

I Can Do Hard Things, or: How Much it Hurt to Run 100.6 Miles

[I Can Do Hard Things was also published by Chicago Athlete Magazine on October 30, 2018.]

“I am DONE WITH THIS BULLSHIT,” Ben screamed at me. “Get up, get moving, and FINISH THIS RACE.”

I slouched in a dirty folding chair at the Mile 86 aid station of the Kettle Moraine 100 Miler on Wisconsin’s Ice Age Trail. I had been running for about 24 hours: my feet were covered in torn blisters, my shorts had shredded my thighs, and my quads were failing. I had sprained my left ankle, I was in a severe calorie deficit, and minutes ago I had made no attempt to avoid collapsing when I felt my legs buckle. Any willpower I had left was locked behind a door in my head. There was no way I was moving another inch.

The crew — Sharon, Todd, Emily and Ben — looked grim, but Ben, a veteran ultramarathoner, wasn’t having it. He ripped the Mile 86 sign out of the ground and thrust it in my face, incensed that I had accused him of lying about only having 14 miles to go. “YOU. ARE. NOT. QUITTING!” He threw the sign to the ground, shaking with fury.

The door in my head swung open. Anger flushed my face. I pushed myself up. I ran. Hard.

I had fallen in love with the idea of running a 100-mile trail race the year before, when my partner Louisa and I paced parts of this same race for Ben. I was eager with my questions, and his gentle encouragement cemented my desire. I signed up the day registration opened, and (mostly) adhered to a conservative training plan that Ben and Emily put together for me. We built in some important benchmarks: if I ran 150-175 miles a month (while maintaining my run streak), raced a 50k in April, and ran back-to-back 25-milers one weekend in May, I’d allow myself to feel like I had earned the right to be there.

At our pre-race crew meeting the week before the race, I had pointedly warned everyone to not let me quit. If I announced I was “out” at an aid station, I had to go to the next one — 5-10 miles away — before stopping. If I said I felt bad, they were to remind me that it probably wasn’t permanent. If I argued that I was injured, they were to ignore me unless (or until) I couldn’t actually move forward.

At the time, these rules were purely conceptual: contingencies we’d never actually need. And for the first 14 hours, I felt mostly good (often great), certain I would finish. Todd told me I looked strong, and I believed him with little-brother trust, savoring the high fives and laughing at everyone’s “Team Patera” shirts. The crew was calibrated with surgical precision, from Emily fixing my feet, to Ben performing miracles with a buff and a few handfuls of ice. Sharon told me I was an Instagram sensation: #justkeephimalive.

Back at it, the soft crunch of the dirt under my feet lulled me into a deep peace: left… right… left… right… sun, breeze, trees, trail. Everythingwas beautiful.

I ate endless gels and sipped water out of my pack. I wondered if I’d see the moon later. I listened to the birds sing. I counted steps. I fantasized about pizza. I wondered if I’d hear thunder later. I listened to critters skitter about, just out of sight. I thought about doing hard things. I sipped water out of my pack and ate endless gels.

I hadn’t seen another runner for hours when I emerged from the deep woods onto an equestrian trail, surprising two riders. I gasped and smiled, inspired by the majesty of the animals. Louisa would love this. The horses chuffed “hello,” and I trotted on, hoping to remember all of the joyful little moments.

By the time I reached the Mile 62 aid station, the sun had eased below the horizon. I was tired and hurting, but still able to laugh about my blisters. Emily helped me change my socks (by doing it for me) and Todd and Sharon administered chicken broth and bug spray. Everyone assured me that the math was in my favor: I was going to finish well before the 30-hour cutoff. Before long I walked with Ben, my first “pacer”, back out into the night. The assembled crew and spectators cheered (lots of runners give up here) and I pumped my fist, unaware that the wheels were about to come off the wagon.

The problems started almost immediately. Ben wanted to run/walk in time intervals, and he didn’t read my mind that I preferred to count steps to get through tough stretches. He exhorted me to eat, but I was getting sick of the goddam gels. I rolled my ankle — on nothing — and felt the familiar “pop” of a sprain. It occurred to me that even if I got really hurt, we were still miles and miles away from, well, anything.

Emily took over pacing duties around Mile 70, and I delightedly shouted “bring it!” to the sky when a midnight thunderstorm erupted. We settled into a good groove, clicking off the miles, telling stories and counting steps. Then, of course, I tripped — on nothing — and face-planted into the mud. The boyish giddiness of running in the rain evaporated. Now, I was convinced that if we went too fast I’d knock my front teeth out.

By the time Todd joined me around mile 77, I was hemorrhaging willpower. Everything was wrong: my shorts tore at my thighs, my headlamp was too dim, my feet refused to land where I wanted them to land. We lumbered for four miles — an endless uphill slog — to the last turnaround point of the day. I announced that I didn’t think I could go on.

Sharon immediately pointed out that quitting without advance notice was against my own rules, and Louisa told the crew that I’d never forgive anyone (including myself) if my race ended now. I desperately needed calories, but the thought of eating turned my stomach. In a hushed conversation 10 feet away, the crew hatched a plan. We trudged back onto the trail, and Todd fed me one Swedish fish every minute or so until they were gone.

Running was out of the question — we focused on my not tripping over rocks and roots that, 22 hours ago, I would have ignored completely. I fell anyway and, lying on the ground, pleaded with Todd to just let me stay there for a while. Within seconds, though, a dense cloud of mosquitos swarmed my legs and arms. I scrambled to my feet. The misery was abject.

The chafing was so bad that I spent the next four miles with my hands in my shorts, just trying to keep the fabric away from my skin. Every hundred steps I asked Todd how close we were to the aid station. “Almost,” he’d say, borderline cheerful. “Just, uh… around this, um—HEY, did you hear that OWL?” (I didn’t hear. I had fallen asleep leaning against a tree.)

We finally arrived at the checkpoint well after dawn, and I told the crew I was done. They fed me soup; I said I was done. They changed my shoes; I said I was done. They helped me into chafe-free sweatpants; I said I was done. Ben said I could quit if I did it at the trailhead. Fine. I staggered over and, feeling my legs buckling, embraced the collapse. Surely they wouldn’t try to make me go on now.

The crew dragged me back to the chair and made me eat some potatoes. I mumbled something about having made peace with giving up. That’s when Ben snapped.

Running is a joyful experience for a lot of people, but not for me. Louisa bounces around like a little girl on every run, meeting new friends, saying hello to the ducks and the trees, dancing to the music in her headphones (or in her head). Me? I could say I like the runners’ high (or more honestly, the simple relief of stopping.) I could say that I enjoy the connection with the road or the trail, or that I enjoy tracking my workouts.

But, really? Anyone who signs up for this insanity is running from something. And while Ben’s rage had broken open the door to my last reserves of will, my demons were waiting in that room, too. Pushed to exhaustion, I couldn’t fend off their taunts: You’re still fat. You’re not good at your job. You’re not smart, or funny. And you certainly don’t belong here. Poor Sharon. She had signed up to run a few miles in the woods with me, not conduct therapy.

I had six hours to complete the last 14 miles: I could have crawled and made it before the cutoff. But the crew had confiscated my watch and — deeply confused about the math and convinced that time was running out — I frantically barked questions at Sharon. What’s our pace? How much further?! WHAT TIME IS IT?! “Time to eat this gel,” she’d say, in the tone of a dear friend who has forgone sleep 26 straight hours to indulge your inferiority complex. “I don’t want to see any more of your tomfuckery at the next aid station.”

The day before, the sun had been friendly, gently greeting the runners after a chilly morning. Now, a day later (had I really been running for 28 hours?!), it clawed my face. Mile 94. The rocky hills — truly “death by a thousand paper cuts” — pulverized my bloody feet as Ben coaxed me up the rest of the 8,801 feet of climbing. Mile 95.

Mile 96.

“You see that guy up there? Don’t let him beat you. Let’s catch him.” He handed me another gel. I ate half of it, dry heaved, and asked Ben for some quiet time.

Mile 97.

Mile 98.

“I’m proud of you.”

Mile 99.

I find some legs when the finish line appears, and Ben peels off. I hear my friends before I see them, and only now does it actually feel like I’m going to make it.

Mile 100.

I high-five the race director and crumble to the ground. I hear Todd say, “That. Was. Awesome.” Someone (me?) is crying. I think about a mantra, taught to me years ago: I can do hard things.

The Numbers

100.6 miles

8,801 feet of climbing

29 hours, 12 minutes

51 gels, 17 Cliff bars, ~20 liters of water, and lots of other food

~19,000 calories burned

3 black toenails

1 sprained ankle

many, many blisters

Escaping the Big Guy Box (Part 2: Nice Bell! / Triathlon)

At 4am on June 10, 2012, I was standing in an elevator in Grand Rapids, on my way to what was undoubtedly going to be the hardest thing I’d ever done: my first triathlon. I was so nervous I thought I might throw up.

Six months earlier I was on top of the world. I had lost more than 60 pounds, run 1,000 miles, and completed two marathons. I had almost entirely ditched all of the insecurities of my former “big guy” identity. Almost, because my nemesis Self Doubt suddenly showed up in that elevator like it had just realized it was way behind on its bullying schedule.

Whoa, heyyy buddy, what are *you* doing here?! You don’t actually *really* know how to swim—remember when you almost drowned that one time? And you just bought that bike three months ago! Plus, you look really bad on a standalone 10K—can’t wait to see how much worse you’ll be running after a swim and a bike! And are you here by yourself?! Who’s going to carry you home if they have to fish you out of the water? Oh, and: cool shorts, bro.

A racer in his mid 40s stepped into the elevator.

I tried to make small talk: “nice bike!” I was pretty naive, but I could tell that his Cervélo probably cost about twice as much as my decade-old Honda Accord.

He looked at me, looked at my bike, looked back at me and sneered, “nice, uh… bell” in an exaggerated sarcastic tone. Mine is an inexpensive off-the-rack road bike, and it just happened to have a bell on it when I bought it. So I kept it, since I ride on a busy path sometimes and I don’t want to be the guy who yells at little kids.

“Thanks,” I muttered, as if I didn’t notice he was making fun of me. What kind of jerk says that?

I quietly fantasized about beating him, or watching him get a flat, or just punching him in the head. But later, once I got fifty yards into the swim and realized I wasn’t going to drown, I forgot completely about him and instantly fell in love with a sport.

That day, after a year and a half of losing weight and learning to really push myself, I learned that I don’t give a crap what anyone thinks of me or my bike, and that I’d rather be dead-f’ing-last than still be on the couch. And since then, I’ve endured scary swims, painful bikes, and some really ugly runs in a bunch of different triathlons. I’ve treated myself to some nicer gear, learned how to train better, and have met many really terrific people.

I also learned that it’s possible for a former big guy to learn how to swim, how to bike a little faster, and how to run a little farther. But the most important part was discovering that there’s nothing better than settling into a groove in the open water, coasting downhill in the sunshine, finding my legs in a sprint, high-fiving a friend at the finish line, and remembering: “I can do hard things”.

Escaping the Big Guy Box (Part 1: Marathon)

When we’re little kids, we start putting ourselves in boxes. We’re trying to form our identities, so our boxes are defined by what we do. We say, “I’m in band, I play football, I’m good at math…”

At first, these boxes are like chalk on the sidewalk, and we can step outside them at any time. The problem with these boxes, though, is that—as we get older—the walls get thicker, and it gets much, much harder to get out.

In time, our box is no longer defined by what we do. It becomes the reverse: what we do is defined by our box.

My box was Big Guy. This guy I knew called me “Cupcake”; the jocks on the basketball team called me “Tits”. And for nearly two and a half decades of my life, I lived in my big guy box. Sure, I would try to lose weight. “Take small steps,” my mother would tell me, and I’d try to lose five pounds. I tried to lose five pounds for ten goddamn years. It was like trying to escape from prison with a pencil eraser.

And then something snapped. I felt shame—certainly for being overweight, but even more so about repeatedly failing at small goals. My aspirations were so small I was embarrassed to tell people what they were.

So I decided to start setting crazy goals. If I was going to fail, I at least wanted to fail spectacularly. I wanted to set goals so absurd that people would laugh at me just for trying.

So I decided I was going to run the Chicago Marathon… And the Memphis Marathon… After losing 60 pounds… After running 1,000 miles… In ten months.

Now, if you’re a hardcore runner, you probably don’t think that’s terribly impressive. That’s because no one ever called you “Cupcake” or “Tits”. When you’re a Big Guy, saying you’re going to run 1,000 miles—basically from Chicago to Boston—is like saying you’re going to run to the moon.

But I did run the miles and marathons, and I escaped the Big Guy box pretty convincingly. It turns out, though, that losing that weight was just a byproduct of the real lesson I learned: most of what we perceive to be our limits are nothing but illusions. And when we actually get right up close and challenge them, they usually disappear.

[See Part 2 for “Nice Bell! or How I Found My Way Into the Ridiculous Sport of Triathlon.”]

The Power of Patience

I am often inspired to re-read an article from Harvard Magazine: The Power of Patience: Teaching students the value of deceleration and immersive attention. In it, author Jennifer Roberts responds to the question, In this time of disruption and innovation, what are the essentials of good teaching and learning?

Roberts, an art history professor, describes one of the first steps she requires of students researching a piece of artwork: spend a “painfully” long time—three full hours—looking at it. She writes:

At first many of the students resist being subjected to such a remedial exercise. How can there possibly be three hours’ worth of incident and information on this small surface? How can there possibly be three hours’ worth of things to see and think about in a single work of art? But after doing the assignment, students repeatedly tell me that they have been astonished by the potentials this process unlocked.

What this exercise shows students is that just because you have looked at something doesn’t mean that you have seen it. Just because something is available instantly to vision does not mean that it is available instantly to consciousness. Or, in slightly more general terms: access is not synonymous with learning. What turns access into learning is time and strategic patience.

“Strategic patience” is such a refreshing idea. Our society is addicted to the consumption of information—limitlessly available on the piece of glass in our pocket—and we delude ourselves into thinking we’re smarter because of it. With so many schools scrambling to get iPads in the hands of every kid (and answers Tweeted at every opportunity), it is so easy for schools to forget the difference between the consumption of information and the construction (or discovery) of meaning.

The latter—true learning—always takes time.

Saying Goodbye to an Old Friend

Today I sold my Premier drumkit, and I feel like I’ve parted ways with an old friend.

When my friend Jeremy and I started Caltera School in 2001, our first purchases were music stands, a copy machine, a whiteboard, a couple of amps, a few dozen shiny black folders, and a natural-finish Premier drumset with gold hardware.

In the years they were in regular use at Caltera, those drums were played for hours every single day for lessons, combos, and jam sessions. They were featured in the college audition CDs of many now-legendary Caltera alumni, and I used them myself for the weekly jazz gigs at Quenchers.

When our efforts to move Caltera into its own building failed in ’07, I lifted my spirits by treating my students (and myself!) to a custom Gretsch kit. I stacked the Premiers in the basement, promising them that their useful life wasn’t over.

But the years went by, and they didn’t move much. Last week I felt guilty realizing how long it had been since they’d been played, so I hesitantly posted a “for sale” ad online with some photos.

A man named John called about them several times, and I could tell he knew very little about drums. I could hear the longing in his voice, though, and he showed up right on time to take a look. He was in his late 50’s, with the hands and eyes of someone who’s done a lifetime of hard work.

“They sure are pretty,” he said, running his finger along one of the rims, not knowing what questions to ask.

I told him about the sizes (a 20” kick is pretty versatile), the heads (coated), and the suspension mounts (that my dad drilled out in his shop).

“I want to have a music room,” he said suddenly, looking at the other instruments nearby. “I’m going to invite my friends over so we can play music together. These will be okay for that, right?”

I helped him bring the drums out to his car, and I was touched by how gently he picked each one up and set it in his backseat.

“Can I tell you something?” he asked, shaking my hand. “I was so excited about finally buying myself some drums that I couldn’t sleep last night.”

I miss that drumkit already, but I’m filled with joy knowing that someone is playing them right now. I’m so happy the Premiers have a loving new friend.

Goals are for Losers (and Other Interesting Reads)

I hope that 2016 is off a fantastic start for you!

Like many people, I have always enjoyed using New Year’s Day and the weeks that follow as an opportunity to set goals. I’m a habitual resolution maker (both big and small) with a long history of satisfying successes and disappointing failures.

Working towards the futures we imagine for ourselves is a tricky business, and I enjoy learning about how other people manage their aspirations and ambitions almost as much as I enjoy working with my own. Below are three articles or books that I’ve spent some time with recently.

I. Research for the Goal Setter

If you are a goal setter, spend a few hours reading through Harvard Business Review bloggers Gretchen Gavett and Sarah Green’s linkset: Achieve Your Goals in 2014 — Here’s Research That Can Help. While many of these aim to help us with our professional lives, all are easily adaptable to our personal lives as well.

Gavett and Green write:

Successful people do nine things differently than everyone else.

The rest of us hold ourselves back in five major ways.

But don’t stress! Just change the way you think about stress.

To spot new opportunities, imagine yourself in the future.

And act like a leader before you are one.

Decide what not to do in order to make time for the work that matters.

Keep meetings on track. Please.

Try not to make decisions when you’re nervous.

Money can actually buy happiness (if you give it away).

Give away your time while you’re at it.

Basically, be generous.

And say “thank you.”

Be quiet (sometimes).

Pick the right battles to fight at work.

Challenge yourself with a growth mindset.

Seriously, go to sleep.

And go for a walk, too.

Remember: It’s really hard to change.

II. “Goals are for Losers”

Right now I am enjoying the book How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big: Kind of the Story of My Life, by Scott Adams. Don’t be inclined to dismiss the advice of a cartoonist (Adams is the creator of Dilbert). Adams spent a long time immersed in the business world and has an uncanny ability to distill complex and unconventional ideas into compelling, accessible writing.

In one chapter of his book, “Goals Versus Systems”, Adams writes:

To put it bluntly, goals are for losers. That’s literally true most of the time. For example, if your goal is to lose ten pounds, you will spend every moment until you reach the goal—if you reach it at all—feeling as if you were short of your goal. In other words, goal-oriented people exist in a state of nearly continuous failure that they hope will be temporary. That feeling wears on you. In time, it becomes heavy and uncomfortable. It might even drive you out of the game.

If you achieve your goal, you celebrate and feel terrific, but only until you realize you just lost the thing that gave you purpose and direction. Your options are to feel empty and useless, perhaps enjoying the spoils of your success until they bore you, or set new goals and reenter the cycle of permanent presuccess failure.

Adams argues that systems—things you every day that increase your odds of happiness in the long run—are far more powerful than the limited willpower people typically draw upon when trying to reach “goals”, or things you’re waiting to achieve someday in the future.

III. If You Let Your Goals Become Your Identity, They Might Kill You

Another book I enjoyed recently was “The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking”, by Oliver Burkeman. In his chapter “Goal Crazy”, Burkeman retells the story (as most famously told in the book Into Thin Air) of eight professional and amateur mountain climbers who died attempting to summit Mount Everest, ignoring evidence that their journey had become suicidal.

Bureman references the term “goalodicy”, coined by another climber to describe the syndrome when people become so fixated on their goals that those goals become “not just an external target but a part of their own identities, of their senses of themselves.” Goalodicy leads to “summit fever”:

Mountaineers, of course, do not speak in the corporate language of targets and goalsetting. But when they refer to “summit fever” — that strange, sometimes fatal magnetism that certain peaks seem to exert upon the minds of climbers — they are intuitively identifying something similar: a commitment to a goal that, like sirens luring sailors onto the rocks, destroys those who struggle too hard to achieve it.

A Short Film About a Guy and His Drums (And Why it’s About so Much More)

The Drummer is a short film by director Bill Block starring the real-life (and sadly, recently deceased) New York City session drummer Dave Ratajczak. Block calls the film his “love letter to music”, and tells the story of a struggling drummer, Dave, who cherishes his prized possession: a beat-up 1930’s drumkit. Playing music is blissful for Dave. One day, he takes an enormous risk—and it changes his whole life.

The film deliberately evokes Benny Goodman’s famous performance of Sing Sing Sing (featuring drummer Gene Krupa) at Carnegie Hall in 1938. The concert was a milestone in American history, as it was the first time black and white musicians shared the stage at Carnegie Hall. (Goodman consistently used his fame and power to challenge segregation laws and practices across the U.S. at the same time his music was outlawed in Nazi Germany.)

Benny’s Carnegie Hall Sing Sing Sing is an epic performance—a 12-minute jam with members of the Count Basie orchestra sitting in—that reaches fever pitch several times before an incredible climax. (A near-riot ensues later in the concert when the band seems to indicate there won’t be an encore.)

My mother loved that record. It always brought her joy, but in particularly bad times, it would seem to heal her. As a teen I was always amazed at how a dusty old LP I bought for a dollar at Goodwill could matter so much to someone. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I came to realize how important Benny was for the whole world.

Fictional drummer David connects with those around him and changes himself in the process. Benny Goodman changed the world in 1938, and brought joy to a little living room in Berwyn six decades later. And, Bill Block reminds us of the extraordinarily transformative power of art for both the art maker and the art audience.

My mom would have turned 71 last week. I know she would have loved The Drummer and how it’s all about a guy and his drums, and also about so much more. Happy birthday, mom.